History

I. Leslie George Katz and Thomas Eakins

In 1993, for a modest catalogue history of the Eakins Press Foundation, founder Leslie Katz wrote of himself:

A would-be publisher, he knew what he wanted. He had a sufficient patrimony. The content of the books would match their design. The first two published would set the standard and establish the continuity, such as it might be, of what would follow. One should be a counterpart of Thomas Eakins. The other should be a present-day embodiment of what Eakins was.

Mr. Katz was referring to the books Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman (a perfect facsimile of the 1855 edition) and Message from the Interior by Walker Evans, respectively. Both published in 1966, they represented the beginning of the Eakins Press imprint. For the next three decades, until his death in 1997, Mr. Katz published books of great beauty that, as defined in an early statement of aims, were "selected from classic and contemporary literature and art relevant to values currently embattled. In content and form they defend human excellence. Together they suggest that advanced technology is a tool and not a substitute for intelligence, that modernity need not outmode humane capacity."

Phidias Studying for the Frieze of the Parthenon, Thomas Eakins, c. 1890, oil on wood, 10 5⁄8 x 13 3⁄4 inches, Eakins Press Foundation

Leslie George Katz was born in 1918 in Baltimore, Maryland. His father, Joseph Katz, had recently emigrated from Lithuania and settled into a successful career as an advertising man, where he became an influential figure in the Baltimore political scene with friends like H.L. Mencken, Harry Truman and Adlai Stevenson. Leslie grew up in a household with important American paintings on the walls-among them Thomas Eakins-and early jazz on the turntable (his younger brother, Dick Katz, would become one of the great jazz pianists, and played with Ella Fitzgerald, Benny Carter, Roy Eldridge, and Lee Konitz, among others).

Jane Mayhall and Leslie Katz, Brooklyn, c. 1965. Photograph by Walker Evans © The Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

When he graduated from the Park School Upper School in 1935, Leslie headed to Black Mountain College in North Carolina. There he met his future wife, the poet Jane Mayhall. Students at Black Mountain, in those days, were against the convention of "graduating," and in keeping with that sentiment, Leslie and Jane left after just two years for New York City, where they continued their studies, intermittently, at The New School. They lived in Brooklyn Heights (near Arthur Miller), where Leslie produced plays for a local theater. He was drafted and quickly, honorably, discharged after an injury that involved a fellow soldier dropping a machine-gun on his back. Back in New York City, Leslie's first job, acquired through the generosity and connections of James Agee, involved writing copy for an advertising agency. He soured quickly on the job, and over the next several years wrote for Classic Comics (where he adapted classic tales, like Hiawatha, for the comic book format), as well as speeches for Adlai Stevenson (Joe Katz was the Director of Stevenson's election campaign). Eventually, Leslie was contributing regularly to Arts Magazine, where by 1951 he was Publisher. At the magazine he worked closely with James R. Mellow and Hilton Kramer; both of them would be influential friends for decades to come. It was while working at Arts Magazine in 1956 that Leslie wrote "Thomas Eakins Now," the article that would prove to be a turning point in his life.

In his effort to re-establish a general appreciation of Eakins as one of America's great painters, Leslie wrote, "Time continues to enhance and confirm the particular qualities of his greatness....In art, his kind of originality could make the United States worthy of its heritage." This sentiment, that an individual artist could singlehandedly reinforce that which is best about democracy, would become the guiding principal for Leslie Katz's life, and the credo of the Eakins Press Foundation to this day. The occasion for writing the article would also become a remarkable point of reckoning for Leslie in terms of his relationship with his father, and the practical impetus for starting the Eakins Press.

Leslie's writing of the 1956 Arts Magazine article, besides fulfilling a longstanding dedication to defending Eakins's reputation, was precipitated by the occasion of an exhibition of work by Eakins for sale at the renowned Knoedler Gallery. The sale of a private collection, of that size, of master paintings, sculptures, photographs, and, indeed, palettes, paintbrushes and other items from Eakins's studio, was unusual and provided Leslie with the perfect environment to immerse himself, for nearly a week, in an all but private room with his subject. He wrote passionately about the importance of Eakins to the history of American art, and worked to establish Eakins as a figure to be studied and emulated by current and future generations. At the end of the week, no doubt reeling a bit from the intensity of the experience, Leslie approached the manager of the gallery, somewhat tentatively, with a question: "I hope that you don't think it improprietous of me, but would you mind telling me to whom this marvelous collection belongs?" The gallerist, taken aback, replied, "You mean you don't know? It belongs to your father!"

It turns out that in addition to collecting Eakins (as well as Sloan, Heade, Glackens, Predergast, Blakelock and other important American artists), Joe Katz had purchased the famous Bregler collection from Knoedler years earlier. The collection before Leslie in 1956 was a combination of the Bregler pictures and Joe Katz's previously assembled Eakins paintings. That Leslie had not known of his father's collection, or his obvious passion for Eakins, was not only remarkable anecdotally, but it also provided Leslie with a rare connection to his otherwise frustratingly distant father. In the coming years, Leslie would be essential in organizing the sale of his father's Eakins paintings to Joseph Hirshhorn, where to this day they comprise the nucleus of the Eakins Collection at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C.

II. The Eakins Press Arrives

With the sale of the Eakins paintings and Joe Katz's subsequent death in 1958, there was money to be divided among the siblings. Leslie used his share to start the Eakins Press in 1966. The year before, he had met Walker Evans at a cocktail party and the two struck up a friendship that would last until Walker's death in 1975.

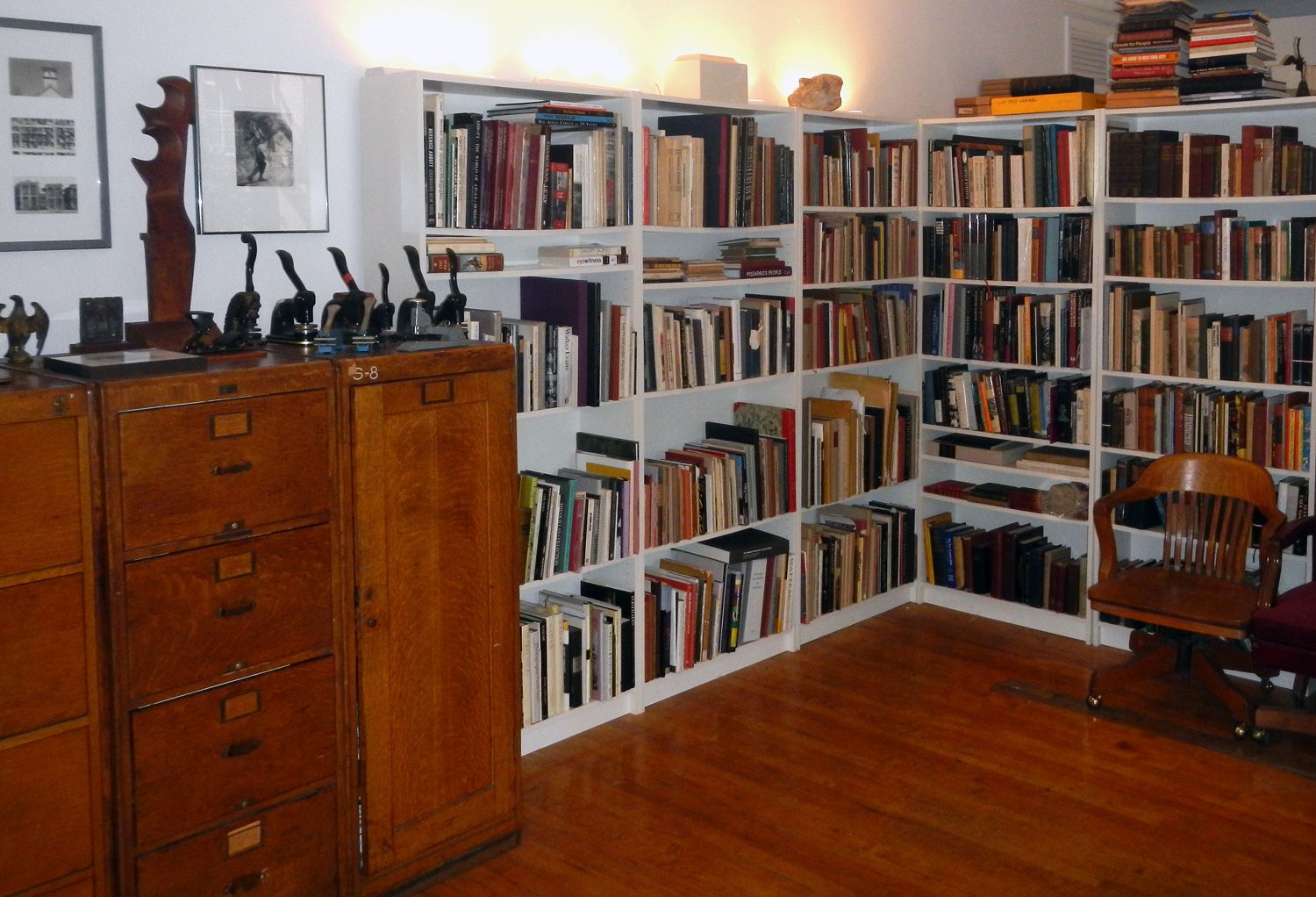

Eakins Press Foundation Office, NY, 2012

A few years later Leslie met Lincoln Kirstein, the founder of the School of American Ballet and the New York City Ballet-the man who brought George Balanchine to America in 1933 and established ballet as a powerful new medium of American art. Kirstein had also been a great proponent of Walker Evans, and had been instrumental in the mounting of the 1938 Walker Evans exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. The Kirstein/Katz friendship proved to be deep and remarkably productive. The Eakins Press would publish, over the next ten years, numerous volumes that were the result of that collaboration with Kirstein: the great monograph Elie Nadelman (1973), Lay This Laurel (1973), The Poems of Lincoln Kirstein, Lincoln Kirstein: A First Bibliography (1978), Lincoln Kirstein: A Bibliography of Published Writings (2007), and a series of books derived from events at the New York City Ballet: Stravinsky Festival (1973), Coppelia (1974), Union Jack (1977), and finally, the catalogue raisonné Choreography by George Balanchine, (1983).

Leslie's strong belief in the role that publishing could play in a democratic ideal led him to publish a number of books in the late 1960s and early 1970s that addressed the issue of what might be called literary heroism. In his introduction to The Bitch-Goddess Success (1968), a collection of essays by Alexis de Tocqueville, Washington Allston, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, William James, Louis H. Sullivan, Charles Ives, Vachel Lindsay, Maxwell E. Perkins, W. H. Auden, John F. Kennedy, and George F. Kennan, Leslie wrote, "Is human character today dominated almost entirely by the rivaling materialities– by science, industry, politics, social revolution, religious canon, by the new chaos of change and environment? As important, to these authors, are the unacknowledged perfidies– and the disinterested heroisms. To them, the individual person is at once the source and the goal of civilization." The text vibrates with relevance, and proves, like so much of what was published by the press in those zeitgeist years, how prescient Leslie was in his use of history as the guiding principal of the present.

A year after the Bitch-Goddess was published, the Eakins Press released Fairy Tales for Computers (1969), a collection of stories and essays by E.M. Forster, Franz Kafka, Theodor Herzl, Samuel Butler, Paul Valéry, and Hans Christian Andersen. In this extraordinary, and again astoundingly prescient collection, Leslie wrote in the introduction–that he modestly signed "The Publishers,"–"In electronic terms [these] stories are prehistoric. Yet every race of beings needs a mythos of tradition: perhaps this collection may be viewed as semi–sacred prophetic writings that will help give computers a sense of religious origin and historic identity."

These books, as well as a volume of the Biblical Gospels edited by Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin's Bagatelles from Passy, served as what can be called truly Patriotic literature: they were not trite self– congratulatory treatises on how grand the United States was, but rather careful, introspective challenges to our society that functioned to both inform and celebrate the potential of democracy.

In 1973, in advance of our nation's Bicentennial celebration, the Eakins Press acquired not–for–profit status in recognition of its educational contributions to American art and letters.

III. The Present Era

I met Leslie in 1990 while I was an undergraduate at NYU. My father introduced me to him with the idea that I might be of some help with the organizing of the Eakins Press Foundation archives (and no doubt, also, that Leslie would be a good influence on me). The first project we worked on was a complete catalogue/anthology of the publications of the Eakins Press, which was published simultaneously with the opening of the exhibition "Message from the Interior, The Eakins Press Foundation, An Exhibition of Books, Portfolios & Related Works of Art," at the Zabriskie Gallery. In her introduction to the gallery catalogue, Virginia Zabriskie, a longtime friend of Leslie's, wrote, "I have often thought, were I to return to this world in another guise, it might be as Leslie Katz, or someone very much like him, who, through books, pamphlets and portfolios, scatters his vision far beyond the parameters of the New York and Paris art worlds, enabling an enduring audience to share and become enriched by them."

"Message from the Interior, An Exhibition of Books Portfolios, and Related Works of Art," Zabriskie Gallery, NY, 1993. Photograph by Jerry L. Thompson

The exhibition was an extraordinary bringing– together of the books of the Press with the objects that inspired them: a selection of photographs by Berenice Abbott, Richard Benson, Matthew Brady, Walker Evans, Alan Fern, Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Baron Adolf de Meyer, Jerry Thompson, Carl Van Vechten, and Carlton Watkins; as well as sculptures by Mary Frank, Raoul Hague, Gaston Lachaise, Elie Nadelman, and Augustus Saint– Gaudens. Of the exhibition, in a review published in The New Criterion in May, 1993, Jed Perl wrote, "[Katz] does not commission painters and sculptors to produce prints to be used as illustrations, but he has taken a number of interests–in sculpture, in photography, in book design, in the history of American art–and allowed them to flow into publications (currently forty– six) that are among the most beautiful books and portfolios ever produced in America."

The Zabriskie show ultimately represented the reinvigoration of the Eakins Press Foundation, and Leslie and I worked together on the promotion of existing projects (in the form of numerous other exhibitions), as well as the development of several new publications, including Walker Evans The Brooklyn Bridge (1994), Walker Evans Incognito (1995), and The Story of the Prophet Jonas (1999).

Leslie died in 1997, but the Eakins Press Foundation continues to publish books, worthy of his mission, that celebrate not just the philosophies of Thomas Eakins, Walt Whitman and Walker Evans, but of Leslie George Katz himself, so that as new publications memorialize the best of art and culture, so too do they continue to embody the spirit of its founding father and his heroes.

Peter Kayafas, Director